| Issue |

Ann. Limnol. - Int. J. Lim.

Volume 57, 2021

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 15 | |

| Number of page(s) | 11 | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/limn/2021011 | |

| Published online | 27 July 2021 | |

Research Article

Can La Redonda lagoon (Cuba) be a suitable habitat for largemouth bass (Micopterus salmoides, Lacepède) recovery?

1

Departamento de Hidráulica, Facultad de Ciencias Técnicas, Universidad de Ciego de Ávila, Carretera a Morón, Km 9, Ciego de Ávila, Cuba: CP: 65100, Mexico

2

Centro de Estudios Geomáticos, Ambientales y Marinos (GEOMAR), Avenida Ejército Nacional 404, Polanco V Sección, CP: 11560 CDMX, Mexico

3

Unidad Académica de Ecología y Biodiversidad Acuática, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, México, CDMX. 04510, Mexico

4

Posgrado en Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México, Mexico, CP: 04510, Mexico

* Corresponding author: mmerino56.unam@gmail.com

Received:

20

April

2021

Accepted:

1

July

2021

For decades, La Redonda lagoon was an excellent location for fishing the largemouth bass (Micopterus salmoides, Lacepède) in Cuba. There are indications that the species disappeared from the lagoon in 2009. Three water surveys were carried out in 2013 and 2014. Physicochemical parameters, including nutrients, were measured in all surveys. Chlorophyll a and water transparency were only measured in November 2013. Results showed that this lagoon is a fresh to brackish water system, with common salinization episodes. There were some hypoxic conditions, but mean dissolved oxygen value was above 5.0 ± 2.8 mg L−1 for the entire survey period. The trophic state was evaluated as oligotrophic and Nitrogen and Phosphorus were limiting in most of the survey sites. The Habitat Suitability Index model (HSI) for largemouth bass had a mean value of 0.63 ± 0.02 (moderate degree of suitability). All results showed that bass recovery could be possible in La Redonda lagoon, but management criteria are necessary. The largemouth bass recovery could help to increase visitations of American anglers to this place and a portion of the revenue could be used to conduct environmental monitoring and studies of the largemouth bass ecology in Cuba.

Key words: Bass / habitat / suitability / lagoon / Cuba

© EDP Sciences, 2021

1 Introduction

The largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides, Lacepède) is rated as the most popular freshwater gamefish in North America. The species is native only to the United States (US), Canada and Mexico, but has been introduced in countries such as Russia, China, France and many others. Largemouth bass are capable invaders, strong competitors, and known predators on native fish species. In Canada, 3.2 million adults fished at least once in inland waters in 2005 (DFO, 2006) and in the United States, inland recreational anglers numbered over 25 million in 2006 (ASA, 2008). In Canada, the contribution to the economy in 2005 was estimated in $7.5 billion, because of the direct and indirect expenditures on recreational fishing (DFO, 2006). In the US, over 767,000 jobs are associated with inland recreational fisheries with a total economic value of $95 billion (ASA, 2008).

The largemouth bass was introduced to Cuba in 1927 into freshwaters near of Havana region (Howell Rivero, 1937) and spread throughout the country rapidly. The species quickly adapted to habitats like reservoirs, natural freshwater lagoons and rivers. This species became a gamefish in 1969 and tournaments and fishing records showed the development of skills among national fishermen to target this new species of Cuban ichthyofauna (INDER, 1969).

La Redonda (Cuba) is a natural brackish lagoon, surrounded by dense mangrove forests and is connected to Los Perros Bay through a tidal channel that has been restricted by a road for 30 years (La Pesquera road). Los Perros Bay also connects to Le Redonda lagoon via pipelines that serve as floodgates. A popular fishery developed in the lagoon during 1980s, primarily for tarpons (Megalops atlanticus) and largemouth bass. This fishery gained international notoriety and attracted many Americans anglers to La Redonda. Beyond fishing, the lagoon offered attractive scenery, with clear water, benthic vegetation (mainly dotleaf water lily, Typha dominguensis and some algae species of the genus Chara). A largemouth bass fishing tournament was held in La Redonda every year from 1987 to 1997, during the month of March. However, by the end of the 1980s, the principal source of freshwater (La Yana watershed) to La Redonda lagoon was affected by the construction of the Puente Largo dam and salinity increased to levels over 3.0 PSU. As water flow was limited, water retention and sediment accumulation increased (more than 50 cm) inside the lagoon; aquatic vegetation began to disappear and water transparency, to decrease (González-De Zayas et al., 2014). Fishing guides noted that largemouth bass number dramatically decreased by 2000 and the last recorded catch of a largemouth bass in La Redonda was in 2009 (González-De Zayas et al., 2014). Eutrophication and harmful algal blooms (Moreira-González and Comas-González, 2014), salinization sedimentation, disease outbreak overfishing or some combination were identified by González-De Zayas et al. (2014) as probable causes of extinction of largemouth bass in La Redonda lagoon.

This study evaluates the physicochemical and trophic state of La Redonda lagoon and its conditions as suitable habitat for largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides, Lacepède).

Our goals were (1) To compare the water quality and trophic state of the lagoon between seasonal surveys; (2) To relate observed water conditions with documented tolerance of those conditions by largemouth bass; and (3) To estimate habitat suitability for largemouth bass through the Habitat Suitability Index (HSI).

The results of this index will be compared with the tolerance ranges reported for largemouth bass, and the potential recovery of the species will be addressed.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study species

Largemouth bass are native to North America. They are capable invaders, strong competitors, and known predators on native fish species. Temperature requirements vary depending on the life stage and activity. The temperature for optimal growth of adult largemouth bass is 24.0–32.0 °C, but growth can occur from 15.0 °C to 36.0 °C (Stuber et al., 1982). Spawning in temperate regions begins when temperature reaches 15.0 °C, particularly after spring and at the beginning of summer. For spawning and incubation, the optimal temperature is 20.0–21.0 °C (Clugston, 1964) with a range of 13.0–26.0 °C (Kelley, 1968). Nests are usually built in firm substrate covered with woody debris or aquatic vegetation in shallow water (<1.5 m). Recruitment of largemouth bass can be mediated by factors such as wind and wave action, water quality, cover, temperature (especially a rapid drop), predation, and human activities (Sammons et al., 1999).

Largemouth bass are more tolerant of low dissolved oxygen and pH than smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieu) (Scott and Crossman, 1973; Lasenby and Kerr, 2000). Largemouth bass avoid waters with dissolved oxygen below 3.0 mg L−1, but can survive at 1.5 mg L−1 when temperatures are optimal (Scott and Crossman, 1973). Levels below 1.0 mg L−1 are lethal (Stuber et al., 1982). According to Stroud (1967), the optimal pH range for largemouth bass is 6.5–8.5. They will tolerate short-term exposure to a minimum pH of 3.9 and a maximum of 10.9; however, bass will not spawn when pH is less than 5.0, and eggs do not survive at pH above 9.6 (Stuber et al., 1982).

Largemouth bass generally inhabit waters that range from fresh to oligohaline (0.5–5.0 PSU) (Meador and Kelso, 1989), although some individuals have been reported for tidal freshwater and estuaries with salinities up to 24.0 PSU (Moyle, 2002; Peer et al., 2006). Klimah (2015) concluded that salinities between 0 and 12.0 PSU alone did not significantly stress or impact estuarine or inland largemouth bass swimming performance. Tebo and McCoy (1964) noted that abundance of largemouth bass declined when salinity was above 4.0 PSU. Embryonic development was impaired at 1.5, and survival was zero at salinities above 10.5 PSU. Some authors (Tebo and McCoy, 1964) suggested that fry growth could decline at 1.7 PSU and was zero at 6.0 PSU.

Spawning in temperate regions begins when temperature reaches 15.0 °C, particularly after spring and at the beginning of summer. Nests are built in the sand, gravel, debris and soft mud near reeds, bulrushes and water lilies. Nests are often built in shallow water (<1.5 m). Other factors such as wind and wave action, water quality, cover, temperature (especially a rapid drop), predation and human activities affect reproduction.

2.2 Study area

La Redonda is a natural lagoon formed by an open water body located (22.2154 N, 78.560 W) north of Moron City, in Ciego de Ávila province, Cuba (Fig. 1). It has an area of about 26.0 km2 and a volume of 13.7 million m3 (Fig. 1). La Redonda is the second most important lagoon (after La Leche lagoon, greatest natural freshwater lagoon in Cuba) in the Great Wetland of the North of Ciego de Ávila (Ramsar site). There are two well defined climate seasons at the study zone: the wet season (from May to October) and the dry season (from November to April). The wet season includes summer and the dry season includes winter.

It is shallow (1–3 m, mean depth 1.5 m) without aquatic vegetation, but is rimmed almost entirely by well-developed mangroves, with prevalence of red mangroves (Rhizophora mangle). The bottom is almost completely covered with a layer of unstable sediment more than 50 cm deep that provides very little physical support. This sediment has a strong organic component that causes a deficit of dissolved oxygen through decomposition in the deeper areas (González-De Zayas et al., 2014).

The sediment layer does not stretch into the mangroves, so there is a shallower broad strip around the entire lagoon where the substrate is firmer and is mainly covered by fallen leaves and mangrove branches. This type of substrate is also found in the channel bed. Salinity is low (<3.0 PSU), but the lagoon still supports salt water species, such as barnacles.

There are several species of microalgae and cyanobacteria, with greater diversity of diatoms. The diatoms present are typical of saline environments, organic matter and eutrophic waters. Desmidian algae also occur at this lagoon (Labaut et al., 2014).

La Redonda lagoon is home to 11 freshwater fish species from eight genera and six families, but only two species are native to Cuba (Nandopsis tetracanthus and Gambusia puncticulata). Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and blue tilapia (Oreochromis aureus) are the main commercial fisheries resources (González-De Zayas et al., 2014). Today, the lagoon is one of the principal freshwater reservoirs of Ciego de Ávila province. The Puente Largo dam (located upstream of the watershed) receives runoff from the La Yana watershed and only small volume of this water reaches La Redonda through regulated floodgates.

|

Fig. 1 Localization of La Redonda lagoon, Cuba. |

2.3 Sampling and analysis

Water samples were collected at 18 sites: twice in 2013 (March and November, dry season) and once in 2014 (June, wet season) (Fig. 1). The sites were located in the central part and the main channels of the lagoon.

Temperature and salinity were determined in situ, using a digital thermo-salinometer (from WLW trade mark). Dissolved oxygen (DO) was determined in triplicate by the Winkler method. Samples for nutrients (dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN = NH4+ + NO2– + NO3–), Soluble Reactive Silicate (SRSi) and soluble reactive phosphorus (SRP)) were immediately filtered through Millipore filters of 0.22 µm and fixed with chloroform. Filtered samples were frozen until analysis, together with unfiltered samples for total nitrogen (TN) and phosphorus (TP). Dissolved nutrients were analyzed with a Skalar San Plus segmented-flow auto analyzer using the standard methods adapted by Grasshoff et al. (1983) and the circuits suggested by Kirkwood (1994). Unfiltered samples for the analyses of TN and TP were held in polypropylene containers and analyzed as nitrate and SRP after high temperature (120 °C) oxidation with persulfate in an autoclave for 30 min, following Valderrama (1981). Organic nitrogen and organic phosphorus were calculated by subtraction (see González-De Zayas et al., 2013 for details). For chlorophyll a (CHL a) samples were taken at 10 sites in November 2013 (Fig. 1) and were analyzed using the fluorometric method of extraction with methanol. Transparency was measured using a Secchi disk.

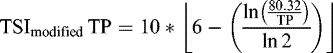

Water quality measurements noted above for November 2013 were used to generate a Trophic State Index for tropical zones (TSI; Carlson 1977, Toledo et al., 1983) that classified the trophic state of La Redonda lagoon. The TSI was calculated using an index for each evaluated parameter (transparency from Secchi disk, TP, RSP and CHL a).

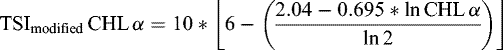

All equations to calculate TSI for La Redonda lagoon are listed below: (1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

TSImodified (mean) was calculated using trophic classification of water taking into account the proposed interval: Oligotrophy ≤44; Mesotrophy 44 < TSI < 54 and Eutrophy ≥54 (Toledo et al., 1983).

Additionally, we used the DIN:TP ratio as an indicator of limiting nutrients using the criteria outlined by Morris and Lewis (1988), where a DIN:TP ratio <0.5 indicates nitrogen limitation, 5 < DIN:TP ratio <4.0 indicates both nitrogen and phosphorus limitation, and DIN:TP ratio >4.0 indicates phosphorus limitation.

2.4 Habitat suitability index (HSI) model

To evaluate La Redonda lagoon as a suitable habitat for largemouth bass, we used the Habitat Suitability Index (HSI) proposed by Stuber et al. (1982) for largemouth bass in United States. We used this index, because there are no largemouth bass in the lagoon at this time and we cannot create a specific model for this lagoon. Also, the model was considered by Stuber et al. (1982) to apply to the species throughout its range in the United States, including southern Florida, which is only 166 km from Cuba. It is applicable across seasons and habitats, and does not establish a minimum habitat size for largemouth bass. We used the lacustrine model that is defined by variables related to several life requisites (Tab. 1).

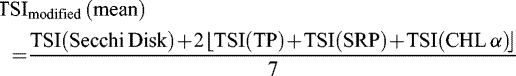

A Suitability Index (SI) was calculated for each habitat variable using SI graphs provided in Stuber et al. (1982). These indices were used to calculate the components (C) of the HSI equation (6)

(6)where CF: Food; CC: Cover; CWQ: Water quality; CR: Reproduction; CF was calculated using level data in summer (from 1990 to 2014) and percent bottom cover 1.0 (e.g., aquatic vegetation, logs, and debris) from González-De Zayas et al. (2014). The bottom cover at La Redonda lagoon is practically zero.

(6)where CF: Food; CC: Cover; CWQ: Water quality; CR: Reproduction; CF was calculated using level data in summer (from 1990 to 2014) and percent bottom cover 1.0 (e.g., aquatic vegetation, logs, and debris) from González-De Zayas et al. (2014). The bottom cover at La Redonda lagoon is practically zero.

For CC, we used the same level data in summer (from 1990 to 2014) and percent bottom cover (e.g., aquatic vegetation, logs, and debris) data, average water level fluctuation (from historic data) during growing season (for fry, juvenile and adults) and depth of the lagoon (<6 m).

CWQ was calculated using some results of our own surveys.

The reproduction component (CR) was calculated using average weekly mean temperature (from our temperature data) in pools or littoral areas during spawning and incubation, the substrate composition (silt and clay) and depth of the lagoon (≤6 m).

Principal life requisites and habitat variables used for lacustrine model for largemouth bass proposed by Stuber et al. (1982).

2.5 Statistical analysis

To determine data normality, a Shapiro-Wilk's W test was performed for all parameters surveyed. Because most data were normalized, we used an ANOVA test and a post-hoc Tukey test to find significant differences among surveys, with season (wet or dry) as an independent effect in the model. The Pearson correlation was used to determine significant correlation among measured physicochemical parameters. Using principal components analysis (PCA), was analyzed total variability of water quality (using measured parameter) and were associated these parameters with spatial distribution. Principal components analysis (PCA) was used to analyze total variability in measured water quality variables. The first (PC1) and second (PC2) principal components from the analysis were plotted to infer spatial differences in water quality. Also, with PCA we identified general tendencies and relationship among water quality variables by examining factor loadings of each variable on PC1 and PC2. STATISTICAL Software (version 10.1) as used to perform the analyses.

3 Results

3.1 Water quality

All results of measured physicochemical parameters are shown in Table 2. Mean temperature for all surveys was 26.1 ± 2.4 °C (22.0–28.8 °C). Temperature showed a seasonal behavior with the lowest mean temperature (significantly different, F = 94.08, p < 0.05) in March 2013 (dry season) and the highest in November 2013 (beginning of winter) and June 2014 (wet season).

Mean salinity for all surveys showed that La Redonda has fresh to brackish water (0.0–3.0) (Tab. 2). Like temperature, salinity followed a seasonal behavior; it was higher in the dry season (March and November 2013) and lower in the wet season (June 2014). Salinity only reached zero during June 2014 and varied spatially in all surveys.

The pH varied widely during the survey period (Tab. 2), without a clear seasonal pattern. The lowest pH was in November 2013 and the highest value (F = 6.09, p < 0.05) was in June 2014. This parameter (pH) showed a spatial pattern; the lowest pH values (<7.50) were recorded on the southern side of the lagoon and the highest (<8.27) in the central portion of the lagoon, which is exposed to winds and light. The pH had a significant correlation with salinity, temperature, DO, SRSi and DIN (Tab. 3).

Dissolved oxygen (DO) varied widely and had lower mean concentration (F = 4.30, p < 0.05) in November of 2013. For all surveys, DO concentrations were above 3.1 mg L−1, except at site 12, where there were hypoxic conditions (<2.0 mg L−1) in March and November 2013. Dissolved oxygen had a significant correlation with temperature, pH and SRSi (Tab. 3).

Ammonium was the principal fraction of DIN (75%). Mean DIN was 4.8 ± 4.3 μmol L−1 for all the survey period. This parameter did not show a clear seasonal pattern. The lowest mean DIN concentration was in November 2013 (dry season), significantly different from those of March 2013 (dry season) and June 2014 (wet season).

Most of TN in La Redonda lagoon was in organic form (90%). Mean TN concentrations varied widely during the survey period (Tab. 2), with significant differences among surveys. The highest mean TN concentration was in March 2013 and the lowest in June 2014. Spatial distribution of TN showed higher concentrations at the northern sites of the lagoon, while lower concentrations were at the center of the lagoon. Total nitrogen only had significant correlation with temperature (Tab. 3).

The SRP concentrations were between 0.5 and 1.8 μmol L−1 for all surveys, with a mean value of 1.0 ± 0.3 μmol L−1 (Tab. 2). The mean SRP was higher in March 2013 than in November 2013 and June 2014. The mean TP concentration was 3.4 ± 0.2 μmol L−1, with a greater fraction (more than 50%) of organic phosphorus. The highest TP mean was in June 2014 and the lowest concentration was in November 2013. The spatial distribution was different in each survey. TP did not show significant correlation with any parameter. Chlorophyll a concentrations were between 0.26 and 3.18 3 μg L−1 with a mean value of 1.38 μg L−1 in November 2013.

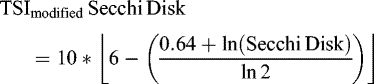

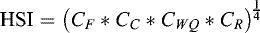

The PCA analysis identified general tendencies and relationships among measured parameters and sampling sites. The two principal components (PC1 and PC2) explained the 56.34% of data variability (Fig. 2). For PC1 (λ = 4.01; 40.10%), salinity (factor loading = 0.75) and DIN (0.48) had the more positive values and pH (–0.88), temperature (–0.84), DO (–0.82) and SRSi (–0.70) had more negative values. For PC2 (λ = 1.62; 16.24%) other measured parameters (with less importance in PC1) had high values: transparency (0.73), TN (0.549, TP (0.53) and SRP (–0.53). The sites located at south of lagoons (inside channels) and at center of lagoons were highly correlated with measured parameters along PC1 axis. Sampling sites located at north of lagoon were highly correlated with parameters along PC2 axis (Fig. 2).

Mean values ± STD and range of physicochemical parameters (for each samplings and mean of all samplings) for three sampled lagoon. Minor letters denoted significant differences between samplings (p < 0.05).

Pearson correlation between all measured parameters in La Redonda lagoon for all samplings.

|

Fig. 2 Principal component Analysis (PCA) of the first (a) and second (b) factors (PC1 and PC2) for survey sites and water physicochemical parameters in La Redonda lagoon. |

3.2 Trophic state index (TSI)

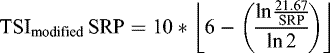

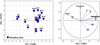

Using equations (1)–(5), we calculated each TSI and TSImean (Fig. 3). La Redonda lagoon was characterized as a mesotrophic system when including Secchi Disk in the TSI and TSImean (26.0) (Fig. 3), but oligotrophic otherwise.

Considering the criterion of Morris and Lewis (1988), 80% of the samples showed that both (nitrogen and phosphorus) are limiting in La Redonda lagoon, while only 12% showed nitrogen limiting and 8% phosphorus limiting.

|

Fig. 3 Mean calculated values of Trophic State Index (TSI) for La Redonda lagoon. |

3.3 Habitat suitability index (HSI) model

The HSI calculated for all surveys was 0.63 ± 0.02 (Tab. 4). This result showed that La Redonda has a moderate degree of suitability for largemouth bass habitat, according to the calculated components. The food component had a low value (0.40 ± 0.02) and the reproduction component was moderate (0.69 ± 0.01).

Values of suitability components and mean Habitat Suitability Index (HSI) for La Redonda lagoon.

4 Discussion

4.1 Water quality and trophic state

La Redonda lagoon can be classified as a fresh to brackish system, with possible episodes of salinization, due to the input of euhaline waters (Batista Tamayo et al., 2006) from Los Perros Bay. These episodes may occur in extreme dry seasons, when water managers restrict supply of freshwater from the Puente Largo dam and the water flow from La Redonda to Los Perros Bay is reversed. Apparently, these salinization episodes could be common due to the presence of species of phytoplankton with a wide variety of environments (fresh, brackish and haline) in the lagoon (Labaut et al., 2014). Another lagoon of the Great Wetland of the North of Ciego de Ávila (GHNCA), Laguna de la Leche, had similar salinity levels (mean salinity of 1.0 PSU), with episodes of salinization due to the input of marine waters through floodgates (Batista Tamayo et al., 2006). However, all salinity values measured in this survey were under 3.0 PSU and at least for this period 2013–2014, the haline conditions of La Redonda lagoon were within the range reported by some authors as normal habitats for the largemouth bass (Moyle, 2002; Peer et al., 2006).

Although there was one site with low DO concentrations, other sites maintained suitable and high levels of DO. It is not uncommon for DO to vary among Cuban reservoirs (Seisdedos et al., 2017; Domínguez-Hurtado et al., 2019) or within the range natural range of largemouth bass. Therefore the observed levels of dissolved oxygen should not impair the habitat suitability for largemouth bass.

Nutrient (dissolved and totals) concentrations in La Redonda were lower than in other studied Cuban freshwater reservoirs (Tab. 5). Most Cuban dams receive great volumes of polluted waters from populated and industrial areas, or high quantities of N and P from agricultural runoff, dominated by sugar cane fields and pasture grasses (Laiz et al., 1994; Betancourt et al., 2010; Rodríguez-Tito et al., 2017). However, contributions of N and P to the lagoon are probably related to the opening of floodgates in Puente Largo dam, which receives all N and P from catchment and acts as a nutrient trap. Dams increase water retention and rates of degradation and sedimentation of particulate organic matter. The new impoundment and reservoirs become effective nutrient sinks (Stockner et al., 2000). When compared with other tropical reservoirs (in United States and Mexico), nutrient concentrations in the lagoon are similar or even lower than at these sites (Tab. 5).

La Redonda lagoon was characterized as an oligotrophic lagoon, with very limited nutrients (N and P) and low levels of chlorophyll a. The lagoon has no direct human or natural water supplies, and the Puente Largo dam controls most nutrient and organic matter from catchment. Since the end of the 1980s, nutrients and organic matter have probably come from internal processes and recycling. Mean concentration of chlorophyll a (1.4 μg L−1) showed oligotrophic conditions (according to Straškraba et al., 1979) in the lagoon (Labaut et al., 2014). While, using the limits proposed by OECD (1982) for chlorophyll a and for TP La Redonda lagoon can be classified as oligotrophic.

Most of other Cuban reservoirs (Tab. 5) are classified as eutrophic; some of these studies used the index of our study (Betancourt et al., 2010; 2012). These reservoirs were influenced by important discharges of nutrients and organic matter from populated and industrial areas and from agriculture. Similar results, eutrophic conditions and anoxia, were found by Ramírez Zierold et al. (2010) for the Valle de Bravo dam (México) and Ledesma et al. (2013) at the Río Tercero dam (Argentina), due to nutrient contribution from rivers and sewage from populated areas located in the catchment.

Nutrients concentration at La Redonda lagoon and at some others freshwater systems in Cuba and the world.

4.2 Suitable habitability for largemouth bass

Previous studies of the Cuban largemouth bass populations are scarce (Guerra et al., 1980; Prokes et al., 1981). However, it is known that largemouth bass adapted very well to Cuban water conditions and is present in most reservoirs and rivers of the country. It was so in La Redonda, but the causes of the largemouth bass extinction in this lagoon are not known.

The results of our work show that all studied parameters are within the ranges found in many studies of this freshwater species. Temperature range of our study was suitable for all life cycles of the species, including spawning. The existence of large areas of the lagoon covered by mangroves prevents a significant increase of temperature during daytime. Boucek et al. (2017) found that micro-refuges and vegetation helped maintain suitable water temperature of 23 Florida lakes for largemouth bass. French (2016) found that a temperature range between 20.0 and 27.0 °C was good for the largemouth bass at Lake Ridge in Illinois. Such values are similar to those of our work.

Salinity range at La Redonda was 0–3.0 PSU, which has been reported as suitable for largemouth bass by some authors (Meador and Kelso, 1989; Peer et al., 2006; Klimah, 2015). However, there is evidence that some salinization episodes at La Redonda could increase salinity up to values not tolerated by largemouth bass juveniles, which can experience osmoregulation and growth problems (Lowe et al., 2009). The frequency of these episodes has not been thoroughly studied at La Redonda, so there is no available data to support how much salinity increases during the episodes or describe salinity distribution in the lagoon. Drought events have been common since the 1980s (Vidal Olivera et al., 2015) and salinity in La Redonda may have increased when salinity rose in a connected lagoon, Laguna de la Leche. In 1988, the mean salinity of Laguna de la Leche was 20.0 PSU with an extreme increase up to 50.0 PSU, which were much greater than that measured between 2004 and 2006 when salinity was 25.0 PSU or in 2010 when salinity was 15.0 PSU.

Before 1988, La Redonda could have strongly impacted its trophic state due to large contributions of nutrients and organic matter from La Yana watershed, but after the construction of the Puente Largo dam, water inputs from the said watershed were restricted to very low volumes (Vidal Olivera et al., 2015). This process could have produced an important impact (possible reduction) on the trophic state of La Redonda (there are no previous studies). Studies on the largemouth bass habitat requirements (Stuber et al., 1982; Brown et al., 2009) do not address water nutrient contents and trophic state. Zachary et al. (2010) found a direct relationship between common carp abundance and increasing nutrient concentrations, while abundance of the largemouth bass decreased under such conditions in 129 lakes of Iowa (USA). However, Maceina and Bayne (2001) suggested that the largemouth bass recruitment decreased due to oligotrophication in one Georgia reservoir; growth rates of age-4 and older largemouth bass and the relative weight of preferred–memorable (38–51 cm) fish also declined. Bachmann et al. (1996) and Boucek et al. (2017) found that the total fish biomass per unit area (including largemouth bass) was positively correlated with total phosphorus, total nitrogen and chlorophyll a, while temperature did not have a significant influence on the individual performance of the largemouth bass in some Florida lakes (USA). Therefore, the oligotrophic or mesotrophic status of La Redonda Lagoon should support this species.

The HSI is a tool for assessing relative habitat availability, and has been widely used by many authors for some freshwater species like the largemouth bass (Brown et al., 2009; Love, 2011; Oyugi, 2014). However, these studies combined some published models with field data (Love, 2011; Hijuelos et al., 2016) or developed new models and indexes (Bain and Jia, 2012). In Cuba, there are no studies on habitat suitability criteria for freshwater species, and in the case of La Redonda, largemouth bass is no longer present. For this reason, we used the HSI proposed by Stuber et al. (1982) as a better approach to evaluate habitat of this lagoon, including components as food, cover and reproduction.

Mean calculated HSI for La Redonda showed that the water quality component had a high degree of suitability, i.e. good water conditions. However, it is not so particularly for the food component and for the reproduction component (moderate). During the early life stages, the diet of fry and juveniles of largemouth consists mainly of micro crustaceans and small insects, juveniles consume mostly insects and small fish, and adults feed primarily on fish and crayfish (Stuber et al., 1982), which are relatively abundant in La Redonda lagoon (González-De Zayas et al., 2014). Stuber et al. (1982) used only one variable for this component in lacustrine habitats: total dissolved solids (TDS). This could be a limitation in the case of La Redonda, where high organic matter in sediments due to mangrove litter deposition, stable margin vegetation and channels are ideal habitats for insects (principally of the family Chironomidae), fry and juveniles of other fish species (of the genus Oreochromis and Cyprinus) and small fishes as Gambusia puncticulata (González-De Zayas et al., 2014).

The reproduction component (CR) in the HSI model has a moderate value. The absence of submerged aquatic vegetation, gravel and high abundance of exotic species as Clarias gariepinus (omnivorous and strong predator) could be factors that affect the largemouth bass reproduction, which have not been studied. Some authors documented important relation among abundance of submerged and emergent aquatic vegetation with nesting black bass (Kramer and Smith, 1960; Chew, 1974), as refuge from predation for juvenile bass (Miranda and Hubbard, 1994; Miranda and Pugh, 1997; Paukert and Willis, 2004) and abundance of largemouth bass (Iguchi et al., 2004; Love, 2011; Hijuelos et al., 2016). Oyugi et al. (2014) found that largemouth bass population in an African lake displayed a niche-restricted spatial distribution, where its stocks were only pronounced in areas with sandy/rocky substrates. For these reasons, we recommend dredging of the lagoon areas to reduce sediment volumes, building of a wooden structure and placement of gravel and rocks in some areas of La Redonda to create spawning sites for the species (Houser, 2007). Also, these artificial structures could enhance the protection of largemouth bass in earlier stages from predators such as Clarias gariepinus.

4.3 Some considerations on the largemouth bass recovery

Cuba has a long experience in aquaculture of freshwater species. In 2001, approximately 200 million of fry of different species (particularly carp and tilapia) were produced (Coto and Acuña, 2007). There are approximately 400 ha of nursery ponds throughout the country, one on them near La Redonda lagoon.

The production of largemouth bass fry at a nursery pond in the outskirts of the town of Morón city can be possible using local or imported breeders, previously certified by the corresponding authorities. Every year, a certain number of fry should be introduced and specialists must study fry survival. With these results, tourism, fishing and water management authorities of the province must work to re-introduce the largemouth bass in the lagoon. For a complete recovery of the largemouth bass fishing in La Redonda, some actions must be taken, namely: a complete ban of largemouth bass harvest; enforcement to prevent illegal fishing, regardless species; use of selective fishing gear for commercial species (catfish and tilapia); avoid the reversal of fluxes from Los Perros Bay building new floodgates in La Pesquera road; establish an ecological water supply from the Puente Largo dam, particularly during the dry season; as well as other management actions (Lowe et al., 2009). Monitoring is also necessary, not only in La Redonda lagoon, but also in other dams such as Hanabanilla, Leonera, Muñoz, where largemouth bass fishing is still a local resource. Revenues from largemouth bass fishing are one of the Cuban government strategies to diversify and increase tourist options, which can draw anglers particularly from the United States.

5 Conclusions

La Redonda lagoon is a fresh to brackish water body that became famous as an exclusive largemouth bass fishing place during the last decades of the 20th Century. There are no studies about the causes of the largemouth bass extinction in the lagoon. In this study, we found environmental conditions that could favor the potential recovery of the largemouth bass, in spite of salinization episodes that could affect largemouth bass populations (particularly fry and juvenile). The calculated value of the HSI for the largemouth bass and the good water conditions of the lagoon support the idea that recovery of this species in La Redonda is possible. This is the first study about the water quality and trophic state of La Redonda lagoon, so it is critical to implement an efficient environmental monitoring program at this reservoir.

Funding

This research was funded by the Territorial Program “Sustainable Tourism in Cuba”. Project code P211LH005-013.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Vicente O. Rodríguez for revising the manuscript in English and to Idea Wild for laptop and digital camera support. We also thank to the anonymous reviewers that contributed to improve our manuscript.

References

- American Sportfishing Association (ASA). 2008. Sportfishing in America: An Economic Engine and Conservation Powerhouse. Produced for the American Sportfishing Association, with funding from the Multistate Conservation Grant Program by Southwick Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Arpajón Y, Larrea Murrel J, Rojas Hernández N, Heydrich Pérez M, Lugo Moya D. 2012. Efectividad de los programas de preservación de ecosistemas dulceacuícolas de Sierra del Rosario, Pinar del Río. Cuba Salud 2012. ISBN 978-959-212-811-8 p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann RW, Jones BL, Fox DD, Hoyer M, Bul LA, Canfield DE. 1996. Relations between trophic state indicators and fish in Florida (USA) lakes. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 53: 842–855. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bain MB, Jia H. 2012. A habitat model for fish communities in large streams and small rivers. Int J Ecol 12: 1–8. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Batista Tamayo LM, González de Zayas R, Zúñiga Ríos A, Matos Pupo F, Hernández Roque L, González Alfonso D. 2006. Atributos físicos del norte de la provincia Ciego de Ávila. In: Pina et al. (editores), Ecosistemas costeros: biodiversidad y gestión de recursos naturales. Compilación por el XV Aniversario del CIEC. Sección I. Ecosistema del norte de la provincia Ciego de Ávila. CIEC. Editorial CUJAE. ISBN: 959-261-254-4. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt C, Suárez R, Toledo L. 2009. Ciclo anual del nitrógeno y el fósforo en el embalse Paso Bonito, Cienfuegos, Cuba. Limnetica 28: 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt C, Suárez R, Toledo L. 2010. Variabilidad iónica y características tróficas del embalse de Abreus, Cuba. Limnetica 29: 341–352. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt C, Suárez R, Jorge F. 2012. Influencia de los procesos naturales y antrópicos sobre la calidad del agua en cuatro embalses cubanos. Limnetica 31: 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Boucek R, Barrientos C, Bush MR, Gandy DA, Wilson KL, Young JM. 2017. Trophic state indicators are a better predictor of Florida bass condition compared to temperature in Florida's freshwater bodies. Environ Biol Fishes 100: 1181–1192. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TG, Runciman B, Pollard S, Grant ADA. 2009. Biological synopsis of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Can Manuscr Rep Fish Aquat Sci 2884: v + p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson RE. 1977. A trophic state index for lakes. Limnol Oceanogr 22: 363–369. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chew RL. 1974. Early life history of the Florida Largemouth Bass (volume 7). Tallahassee: Florida Game and Freshwater Fish Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Clugston JP. 1964. Growth of the Florida largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides floridanus (Lesueur), and northern largemouth bass, M. salmonides (Lacepede), in subtropical Florida. Trans Am Fish Soc 93: 146–154. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coto M, Acuña W. 2007. Freshwater fish seed resources in Cuba, pp. 219–231. In: M.G. Bondad-Reantaso (ed.), Assessment of freshwater fish seed resources for sustainable aquaculture. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. No. 501. Rome, FAO. p. 628. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). 2006. 2005 Recreational Fisheries Survey Summary. Ottawa: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, pp. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Hurtado IM, Soto-Valero C, Machado-Montes de Oca A, Salmón-Cuspinera Y. 2019. Influencia de factores meteorológicos en la acuicultura de aguas interiores. Rev Cubana Meteorol 25: 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- French CG. 2016. Behavior and habitat selection of largemouth bass in response to dynamic environmental variables with a focus on dissolved oxygen. Master of Science in Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences. University of Illinois. pp. 100. [Google Scholar]

- González-De Zayas R, Merino-Ibarra M, Soto-Jiménez MF, Castillo Sandoval FS. 2013. Biogeochemical responses to nutrient inputs in a Cuban coastal lagoon: runoff, anthropogenic, and groundwater sources. Environ Monit Assess 185: 10101–10114. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-De Zayas R, Lestayo González JA, López Rojas M. 2014. Rescate de la actividad de pesca de la trucha en laguna La Redonda. Informe final. pp. 68 [Google Scholar]

- Grasshof K, Ehrhardt M, Kremling K. 1983. Methods of seawater analysis. Verlag CEIME. II Edición. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra FP, Pérez AM, Prokes M. 1980. Spawning, early development and growth of largemouth bass in Cuba. Acta Sci Natural Acad Scientiarum Bohemoslovacae-Brno 14: 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hijuelos AC, Moss L, Sable SE, O'Connell AM, Geaghan JP. 2016. 2017 Coastal Master Plan: C3-18–Largemouth Bass, Micropterus salmoides, Habitat Suitability Index Model. Version II. 1–25. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Houser DF. 2007. Fish Habitat Management for Pennsylvania Impoundments. Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Howell Rivero L. 1937. The introduced Largemouth Bass, a Predator upon Native Cuban Fishes. Trans Am Fish Soc 66: 367–368. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi K, Matsuura K, McNyset KM, Peterson AT, Scachetti-Pereira R, Powers KA, Vieglais DA, Wiley EO, Yodo T. 2004. Predicting invasion of North American basses in Japan using native range data and a genetic algorithm. Trans Am Fish Soc 133: 845–854. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- INDER (Instituto Nacional de Deportes, Educación Física y Recreación). 1969. Calendario de Recreación Deportiva 1969. INDER, La Habana, pp. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley JW. 1968. Effects of incubation temperatures on survival of largemouth bass eggs. Prog Fish-Cult 30: 159–163. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood DS. 1994. Sanplus segmented flow analyzer and its applications, Seawater analysis. Skalar. pp. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Klimah CA. 2015. Swimming Performance of Coastal and Inland Largemouth Bass at Varying Salinities. Master of Science. Graduate Faculty of Auburn University. pp. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer RG, Smith Jr LL. 1960. First-year growth of the Largemouth Bass, Micropterus salmoides, and some related ecological factors. Trans Am Fish Soc 89: 222–233. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Labaut Y, Betancourt C, Comas A, Salvat H, Toledo L. 2014. Microalgas bentónicas de la laguna La Redonda y su relación con las características del ecosistema. Rev Cubana Investigaciones Pesqueras 31: 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Laiz O, Quintana I, Blomqvist P, Broberg A, Infante A. 1994. Comparative limnology of four Cuban reservoirs. Int Revue gesamten Hydrobiol Hydrogr 79: 27–45. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lasenby TA, Kerr SJ. 2000. Bass transfers and stocking: An annotated bibliography and literature review. Fish and Wildlife Branch, Ontario Ministry of Natural resources. Peterborough, Ontario. 207p. + appendices. [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma C, Bonansea M, Rodríguez CM, Sánchez Delgado AR. 2013. Determinación de indicadores de eutrofización en el embalse Río Tercero, Córdoba (Argentina). Rev Ciência Agron 44: 419–425. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Love JW. 2011. Habitat suitability index for largemouth bass in tidal rivers of the Chesapeake bay watershed. Trans Am Fish Soc 140: 1049–1059. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe MR, DeVries DR, Wright RA, Ludsin SA, Fryer BJ. 2009. Coastal largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) movement in response to changing salinity. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 66: 2174–2188. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maceina MJ, Bayne DR. 2001. Changes in the Black Bass Community and Fishery with Oligotrophication in West Point Reservoir, Georgia. North Am J Fish Manag 21: 745–755. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meador MR, Kelso WE. 1989. Behavior and movement of largemouth bass in response to salinity. Trans Am Fish Soc 118: 409–415. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda LE, Hubbard WD. 1994. Winter survival of age-0 Largemouth Bass relative to size, predators, and shelter. North Am J Fish Manag 14: 790–796. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda LE, Pugh LL. 1997. Relationship between vegetation coverage and abundance, size, and diet of juvenile Largemouth Bass during winter. North Am J Fish Manag 17: 601–610. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira-González A, Comas-González A. 2014. Blooms of a Chattonella species (Raphidohyceae) in La Redonda Lagoon, Northeastern Cuba. Harmful Algae News 48: 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Morris DP, Lewis WM. 1988. Phytoplanckton nutrient limitation in Colorado lakes. Freshw Biol 20: 315–327. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moyle PB. 2002. Inland Fishes of California. Los Angeles, CA: Univ. Calif. Press, 502pp. [Google Scholar]

- Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico (OECD). 1982. Eutrophication of Waters. Monitoring, Assessment and Control. Cooperative Programmers on Monitoring of Inland Waters (Eutrophication Control), Environment Directorate, OECD Paris, Final Report. France. [Google Scholar]

- Oyugi DO, Mavuti KM, Aloo PA, Ojuok JE, Britton JR. 2014. Fish habitat suitability and community structure in the equatorial Lake Naivasha, Kenya. Hydrobiologia 727: 51–63. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Paukert CP, Willis DW. 2004. Environmental influences on Largemouth Bass Micropterus salmoides populations in shallow Nebraska lakes. Fish Manag Ecol 11: 345–352. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peer AC, De Vries DR, Wright RA. 2006. First-year growth and recruitment of coastal largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides): spatial patterns unresolved by critical periods along a salinity gradient. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 63: 1911–1924. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Popowski G, Campos A, Sánchez M, Borrero N, Gómez R, Pérez M. 1994. Desalinization effects over planktonic community structure in Laguna de la Leche, Cuba. AVICENNIA. Rev Ecol Oceanol Biodivers Trop 2: 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Prokes M, Barus V, Libosvarsky J. 1981. Some results of the research on Cuban freshwater fishes. In: Topical problems of ichthyology: proceedings of the symposium held in Brno, March 22–24, 1981 (p. 101). Institute of Vertebrate Zoology, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Zierold JA, Merino-Ibarra M, Monroy-Ríos E, Olson M, Castillo FS, Gallegos ME, Vilaclara G. 2010. Changing water, phosphorus and nitrogen budgets for Valle de Bravo reservoir, water supply for Mexico City Metropolitan Area, Lake Reserv Manag 26: 23–34. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Tito JC, Pérez-Silva RM, Gómez-Luna LM, Álvarez-Hubert I. 2017. Evaluación químico analítica y microbiológica de los embalses Chalons y Parada de Santiago de Cuba. Rev Cubana de Química 2: 418–435. [Google Scholar]

- Sammons SM, Dorsey LG, Bettoli PW, Fiss FC. 1999. Effects of Reservoir Hydrology on Reproduction by Largemouth Bass and Spotted Bass in Normandy Reservoir, Tennessee. North Am J Fish Manag 19: 78–88. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Scott WB, Crossman EJ. 1973. Freshwater Fishes of Canada. Fish Res Board Can Bull 184: 966. [Google Scholar]

- Seisdedo M, Díaz M, Barcia S, Arencibia G. 2017. Análisis comparativo de la calidad del agua de dos embalses de la cuenca Arimao, Cuba (2014–2015). Rev Cubana Invest Pesq 34: 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Stockner JG, Rydin E, Hyenstrand P. 2000. Cultural oligotrophication: causes and consequences for fisheries resources. Fisheries 25: 7–14. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Straškraba M, Desortová B, Fott J. 1979. Zur Methodik der Bestimmung und Bewertung des Oberflächengewässern. Acta Hydrochim Hydrobiol 7: 569–590. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud RH. 1967. Water quality criteria to protect aquatic life: a summary. Am Fish Soc Spec Publ 4: 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Stuber RJ, Geghart G, Maughan OE. 1982. Habitat suitability index models: Largemouth bass. U.S. Dept Int. Fish Wild. Serv. FWS/OBS-82/10.16. p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Tebo LB, McCoy EG. 1964. Effect of seawater concentration on the reproduction and survival of largemouth bass and bluegills. Prog Fish-Cult 26: 99–106. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo AP, Talarico M, Chinez SJ, Agudo EG. 1983. A aplicação de modelos simplificados para a avaliação de processo da eutrofização em lagos e reservatórios tropicais. XIX Congresso Interamericano de Engenharia Sanitária e Ambiental. Camboriú, 1983, pp. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Valderrama JC. 1981. The simultaneous analysis of total nitrogen and total phosphorus in natural waters. Mar Chem 10: 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal Olivera VM, González-Abreu Fernández R, Jiménez Peña Y, Valdés González LA, Castro Carrillo M. 2015. Funciones y usos de los recursos hídricos en el Gran Humedal del Norte de Ciego de Ávila. Ingeniería Hidráulica Ambiental XXXVI: 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zachary J, Quist MC, Downing JA, Larscheid JG. 2010. Common carp (Cyprinus carpio), sport fishes, and water quality: Ecological thresholds in agriculturally eutrophic lakes. Lake Reserv Manag 26: 14–22. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Cite this article as: González-De Zayas R, Merino-Ibarra M, Lestayo González JA, Castillo-Sandoval FS, Peraza-Escarrá R. 2021. Can La Redonda lagoon (Cuba) be a suitable habitat for largemouth bass (Micopterus salmoides, Lacepède) recovery? Ann. Limnol. - Int. J. Lim. 57: 15

All Tables

Principal life requisites and habitat variables used for lacustrine model for largemouth bass proposed by Stuber et al. (1982).

Mean values ± STD and range of physicochemical parameters (for each samplings and mean of all samplings) for three sampled lagoon. Minor letters denoted significant differences between samplings (p < 0.05).

Pearson correlation between all measured parameters in La Redonda lagoon for all samplings.

Values of suitability components and mean Habitat Suitability Index (HSI) for La Redonda lagoon.

Nutrients concentration at La Redonda lagoon and at some others freshwater systems in Cuba and the world.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Localization of La Redonda lagoon, Cuba. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Principal component Analysis (PCA) of the first (a) and second (b) factors (PC1 and PC2) for survey sites and water physicochemical parameters in La Redonda lagoon. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Mean calculated values of Trophic State Index (TSI) for La Redonda lagoon. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.